Photo of WWI soldiers in the trenches from here.

The teacher’s career has never been under more attack until now, for a variety of reasons, some well-meaning and well-founded, some well-meaning but ill-founded, and others that are sociological and political in nature and thus, beyond the teacher’s control. Is it any wonder then that more and more teachers are leaving the profession? Classrooms are overcrowded more than ever, with students spanning a spectrum in learning abilities, mental health issues among teenagers are on the rise, and schools are understaffed.

As a young teacher back in 2010, I wish someone had sat me down and given me some tips for what I was about to face. Looking back, though, here are some things that I learned along the way. I hope these will prove helpful to those brave souls still hoping to become a teacher, or who in finding themselves currently in the teaching battlefield, can find some much-needed succor and encouragement.

Please keep in mind a few important caveats: This is written from the point of view of a high school teacher. I have limited experience with elementary school students. Also, what I will be suggesting are just that: suggestions. A teacher’s life is one that never ceases from dawn til dusk. When we get home, there’s only more teaching stuff to do–grading, preparing for tomorrow’s class, designing quizzes and tests, providing thoughtful feedback to written homework–in addition to our personal lives. Most of what I suggest here therefore requires advanced planning, preferably planning during the summer before the school year begins. There is nothing worse than preparing an entire class theme or activity the night before when you have either have a family to attend to, bills to pay, or need much needed alone time to yourself to recharge. As teachers know, a teacher’s life is not a career choice; it is a vocation. We’re not only teaching a subject; we are modeling better ways to learn and engage in the world, we are providing emotional support in difficult situations, and many times, we are the only cheerleaders in a student’s turbulent life. Adolescence is a brutal time, and high school is a veritable jungle.

Be compassionate with yourself and take time to yourself, on a daily basis. Schedule time for yourself in your daily calendar and stick to it. Otherwise, burnout can easily occur.

1. It’s no longer the 1990s. Remember going to school when there was no internet? The most you could hope for was dial-up, and that was maybe your senior year in high school if you were lucky. Remember there were no cell phones, tablets, or laptops? So kids who “misbehaved” or didn’t pay attention would either “act out,” stare out the window, pass notes, or doodle in their notebooks. Today’s teacher is competing with all of this PLUS cell phones, tablets, laptops, and the horrifying psychological maelstrom that is social media. As a high school teacher, I had to ask kids to turn off their cell phones in class, since they were perpetually shackled to them. This wasn’t enough though: kids would still leave them on. I had one kid hide her cell phone inside her pencil box and have it open to a page in the online math textbook while taking an exam. I had another student furiously texting in class; it turns out she was having a fight with her mother over text while her mother knew she was in class. I had another student film me.

Solution: Collect cell phones at the beginning of class in a wicker basket. Expect much begrudging, a litany of complaints, and murmurations of “This is so unfair!” to “What if there’s an emergency?” Then the school will call if there’s an emergency (unless of course, it is a dire emergency involving a life or death situation, where for example, a parent’s life hangs in the balance). I promise students will thank you for being disconnected for 48 minutes.

2. Taking notes. Once cell phones have been collected, students will still attempt to get online, with the excuse that they are “used to taking notes on their laptops or tablets.” In a word, no. Just no. Even if this is true for some students, for the majority, they will be checking stuff online and messaging each other. This has two negative consequences. First, the student is not fully present in the classroom. Second, and most importantly, the physical act of taking notes by hand has been shown to not only improve reading skills but vastly enhance learning and memory.

According to Stanislas Dehaene, a psychologist at the Collège de France in Paris, “When we write, a unique neural circuit is automatically activated. There is a core recognition of the gesture in the written word, a sort of recognition by mental simulation in your brain. And it seems that this circuit is contributing in unique ways we didn’t realize. Learning is made easier.”

Solution: Note taking will be done in (gasp) notebooks with (gasp) a pen or pencil.

3. The power of storytelling. We are storytelling creatures. We crave narrative. We want to hear about heroes and villains. We want to learn of underdogs succeeding even when all odds are stacked against them. I think this may go back to our ancestors, who gathered around the campfire to hear a good story while keeping warm, and this has somehow trickled down into our collective unconscious.

Storytelling is obviously easier to do in humanities classes, such as history, literature, or social studies. It becomes dicier, if like me, you are teaching algebra or pre-calculus. This doesn’t mean, however, that you can’t engage in storytelling in math and science; you only have to dig deeper.

The history of algebra is actually extremely fascinating and not something that is ever talked about in high school. Pull your students in with how Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (780-850 C.E.) came up with “algebra” in his treatise Al-Jabr, which people think means anything from “completion,” “balancing,” “reunion of broken parts,” or even “reduction.”

But what spurred al-Khwarizmi to come up with such torment for future high school students? Al-Khwarizmi lived during the Abbasid Caliphate, which gave birth to the Islamic Golden Age, a time that saw an enormous burgeouning in Islamic literature, mathematics, sciences, economics, and political power.

Suddenly, the Abbasid Caliphate saw itself in need of figuring out how to rule such a colossal empire that stretched from Northern Africa, the entire Arabian Peninsula, Iran, a huge chunk of eastern Asia, and parts of Turkey, Georgia, and Russia. How do you calculate where your major Muslim cities are now located geographically? How do you divide estates? How do you come up with a world map of the known world that has accurate measurements of territories and countries? More importantly, how do you determine the times during the day when you had to pray or even the direction to Mecca? While al-Khwarizmi did not exactly invent “algebra,” he did refine the known mathematics of the time, particularly that of the Babylonians and Euclid, to create a more comprehensive and sophisticated system of solving for unknown quantities.

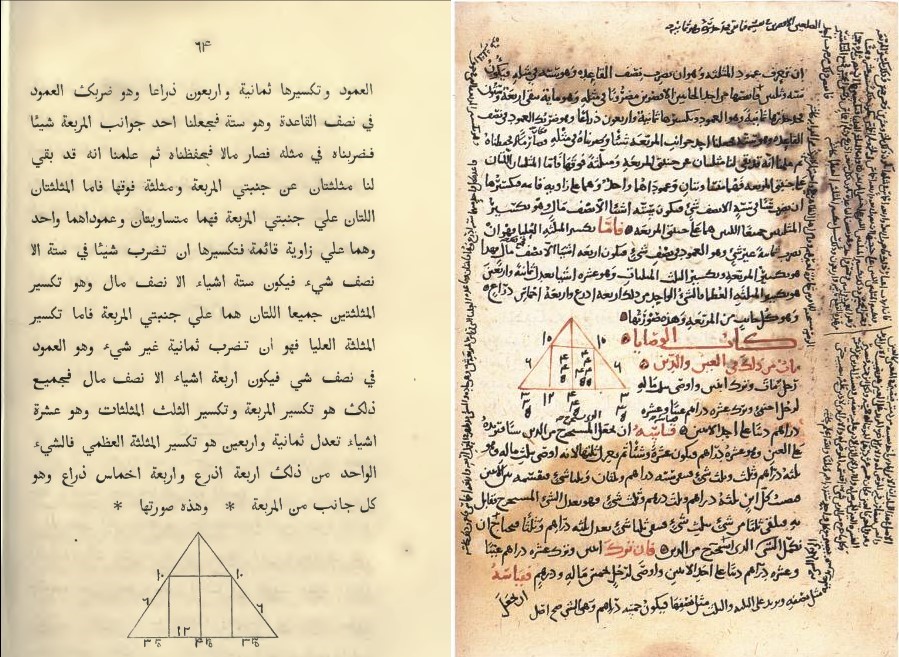

Suggestion: Find a story associated when introducing a new topic. Set the background. Create an atmosphere and mood. Who are your main characters? What issues or problems are trying to be solved? Who comes up with possible solutions and why? Bring in a primary historical source if possible to show. For instance, here on the left is an 1831 translation of the original Al-Jabr work (on the right).

5. Meet your students where they are, not where you want them to be. In your attempt to tell a story to make a class more interesting, knowledge gaps will immediately become glaringly obvious in your students. Wait, who were the Abbasids and how did they get there? Who was Al-Khwarizmi and what was he doing in the House of Wisdom? Worse yet…you find that your students can’t solve a simple algebraic equation because they’re wobbly in their multiplication tables and can’t remember how to do simple arithmetic with fractions.

Meet them where they’re at. If you have to review multiplication tables, arithmetic, and PEMDAS, don’t assign these to be done at home. I’ll assure you, they won’t do it on their own. Do it with them. Model how to do these things in class. Only then, assign homework and make it fun: divide kids into teams and have a math competition the next day, or the next few days.

Pull a Jaime Escalante (1930-2010) if you have to: meet your students at the door and only allow them into the classroom if they can answer a simple math problem correctly. This may get you into trouble with the administration and with parents because in today’s culture, this will be deemed as “too demanding.” It isn’t too demanding. It’s basic knowledge. You’re making the class interactive from the get-go, while reinforcing engagement with the material. Gradually build them up to where you want them to be.

Suggestion: Show your students where you want them to be with a visual, and then work backwards until you meet them where they are. Outline the steps needed to get there. And then make the journey in getting there fun.

6. Engage with your class in a conversational style, using the Socratic Method. People—no matter whether they are children or adults—do not like being preached to nor spoken down to, all the while being silent, and forced to take notes. Paulo Freire (1921-1997), one of the most influential educators of our time, compared classic teaching with a “banking method,” wherein students were viewed as “receptacles to be filled by the teacher” (Pedagogy of the Oppressed, p. 72). Instead, Freire encouraged critical pedagogy, an educational philosophy that encourages students to engage in critical thinking, social action, and self-actualization.

This is challenging, especially when the teacher belongs to a generation so different from the one they’re teaching. For me, I was approaching things from a Gen X perspective to a class full of Zoomers. Instead of imposing your own generation’s way of looking at the world, ask your students how they see the world and why. Everyone loves talking about themselves, especially when they’re “teaching the teacher.” For instance, if you notice your students dozing off and not engaging with the material, bring the material home in a way that resonates with their worldview.

The best example of this was given to me by James Brown-Kinsella, a graduate student in the East Asian Languages and Literatures department at Yale. Fresh from pandemic lockdown and unfamiliar with a college classroom, James’ students were not particularly enthused in discussing Confucian ethics. James then came up with a brilliant question:

“If Confucius existed today, would he be canceled?”

Suddenly, he couldn’t get his students to shut up about Confucius or his ethics. He then pushed it further, “Would it be ethical to cancel anyone according to Confucius?”

I think you can imagine the rest.

Suggestion: Keep abreast of who your students are and how they see the world. If in doubt, ask them. What are they reading? Who are their heroes and why? What heroes and historical figures in your own field of teaching have undergone the same trials and tribulations that you’re experiencing, and what have been their solutions? Someone who has made a career of teaching history using Gen Z terms is Lauren Cella. Just take a look at her videos explaining the Russian Revolution and the Declaration of Independence.

7. Deliberately approach, befriend, and try to understand the troubled students. Teaching is an emotionally taxing profession because we are not only making sure to keep pace with our proposed teaching schedules, meeting knowledge milestones by x date, grading, and creating curriculum while being in a good mood all the time, but we are also paying attention to the students that are acting out, distracted, not turning in their homework consistently, showing obvious signs of mental health issues, arriving high to class because they’re raiding their grandparents’ cabinets for opioids, and going hungry because their parents don’t have enough money to give them lunch money. This makes it very tempting to focus solely on the “good students” while unconsciously (or consciously) ignoring the ones that make our teaching even more challenging than it already is to save ourselves what little energy reserves we have left.

Brit Marling and Zal Batmanglij acknowledged this phenomenon in the their now cult-classic The OA. In the first episode, the character known as “the OA” (played by Marling) poses as a parent to stop a high school teacher, Mrs. Broderick-Allen, from expelling Steve, a bully. During their parent-teacher conference, “the OA” gently reminds Mrs. Broderick-Allen of a teacher’s job:

“I think Steve is lost. But in order to teach him you have to teach yourself again. And you decided somewhere along the way you were done learning. It was too painful to stay open.

If you want to do your job expel the bully. Focus on the kid who sings like an angel even though he doesn’t need you. If you want to be a teacher, teach Steve. He’s the boy you can help become a man.”

It is too painful to stay open, but open we must stay because the other adults in a troubled student’s life are either not present to teach them (any) better or have given up on the kid, altogether.

Suggestion: Pay attention in your classroom. Who seems to be off today? Approach them discreetly, without embarrassing them or creating a spectacle. Talk to them. Ask how they are. Perhaps at first, they’ll say nothing. That’s ok. Keep trying. We always remember the teachers who were there for us, because they changed our lives by caring.

8. Keep hope and awe alive through a growth-mindset. How many times have we heard people say “I’m just not a math person” or “I guess I inherited my parents’ inability to write.” These statements are examples of what Carol Dweck has called a “fixed-mindset,” a view that intellectual abilities are fixed (or that you’re born with/without them, and therefore set in stone) and not mutable. Students with a “fixed-mindset” are reluctant to take on new challenges for fear of assured failure, which then becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Meanwhile, students with a “growth mindset” know that they can change and grow their inborn talents, abilities, and aptitudes through application and experience (Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, page 7).

Turns out intelligence and abilities are not fixed; they can be changed through neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to create new neural connections to learn or adapt to a new set of circumstances or knowledge material. To have an adult, a teacher, someone who “should know better than you” tell you that you’re “just not cut out for x subject” because you “don’t have what it takes” can be catastrophic. This is because maybe that teacher was the last person who could have turned that person’s belief in themselves around. That teacher is the last gatekeeper between the land of “Maybe I can” and the permanent land of “I won’t ever be able to.” The teacher therefore is a source of refuge, solace, and comfort.

I’ve had countless students tell me of past math teachers who made them feel dumb in verbal and non-verbal ways, from telling them outright “Just don’t worry that pretty little head of yours with this; you won’t need it when you grow up” to nonverbal sighs of exasperation, angry expressions, and aggressive correction of mistakes in quizzes and exams. I had this happen to me in high school with my own chemistry teacher, who made sure to let me know I “wasn’t science material” at every possible turn, to the point where she got upset if I got something correct when she was expecting the opposite.

There is enough learned helplessness built into students from their personal and school lives: why become yet another source for wrong confirmation that they are powerless to change a situation? This is equivalent to an unconscious hostile takeover of their self-esteem, before they’ve had a chance to further develop it. Not only that, but educators are only beginning to understand how messages told to students in high school about their abilities (or lack thereof) continue to shape how they view themselves in adulthood.

This is thought to be due to what Megan Stack wrote in the New York Times, when she interviewed Laurence Steinberg, an adolescent psychology expert: “The highs [in adolescence] are higher, the pain cuts harder, and the experiences get stored deeper in the brain. In the end, the aftertaste of those years can cling for decades, and many people struggle to distinguish their adult selves from their adolescent perceptions and memories.”

Suggestion: If a student doesn’t believe in her/him/themselves, step in and believe for them, until they begin to believe in themselves again, or, for the first time in their lives. Don’t judge their mistakes. Be gentle. A growth mindset cannot be grown by judging mistakes or shaming, but by learning from them. Ask them where they think they went wrong and what they could’ve done better. If the task is too hard, scale it back to where they are, and begin from a place where the material is neither too easy nor too difficult to understand, a place that psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) called the “Zone of Proximal Development.” Tiny achievements create cracks of light in a dark tenebrous landscape of no hope.

Tiny achievements build upon each other as well. Ask your student to write down every achievement in a notebook, no matter how tiny, no matter how microscopic. Every day. Even if it was: I got out of bed today. Doesn’t matter. They got out of bed. Period. THAT is an achievement in itself. Build from there.

In time, when a student starts doing well in something they (or their parents, past teachers, friends, or society) previously thought were useless or helpless to change, a sense of awe at their inner strength will emerge. In the end, it’s not that they mastered how to “complete the square” in three different ways or that they finally understood how to write a five-paragraph essay, but that they proved to themselves that they are stronger, more capable, and more resilient than they initially thought.

Stay open, and (un)knowingly, you will save a life.