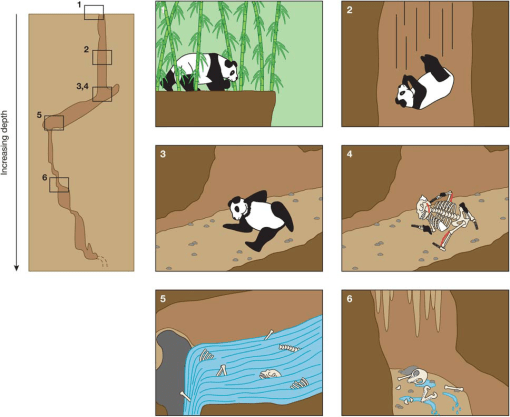

I’ve spent the whole day today reading up on taphonomy, the study of the changes that influence a faunal or archeological deposit. The word was coined by the Russian palentologist Ivan Efremov in a 1940 issue of Pan-American Geologist, and literally means the “laws of burial.”

All taphonomic models emphasize decline in the integrity of the buried remains, which occurs before, during, and after burial. Further decline in integrity occurs during excavation and archaeological biases, which can dictate what’s an “important” find and what’s not. It is a fascinating branch of science and I discovered super curious things today during my reading.

So I’m reading one of the Cambridge Manuals of Archaeology titled simply Zooarchaeology(2005). From the book:

“The deposited [faunal] assemblage contains the durable remains of animals either intentionally buried, thrown on a refuse heap, or lost at the site…Foot traffic across the [faunal] site crushes some of the refuse. The plant and animal refuse attracts scavengers and commensal animals. Animals, such as mice and land snails, find food and shelter at the site and their bodies become part of the assemblage if they die there, along with insects and botanical materials. Other animals living at the site, such as [an] owl roosting in [an] overhanging tree, regurgitate pellets of inedible animal remains that mingle with the debris related to human economic and social life.”

If you thought that was the end of it, we’re only beginning. After all of this happens, post-depositional processes further change the site. For instance plant roots and burrowing animals can alter and move the deposits from one place to another. Displacement also happens thanks to flowing water and wind, each of which carries sediments that can add to the deposit. Finally, as if you weren’t having enough fun yet, there’s something called tephra, which is a fancy word for volcanic ashes. Tephra can blanket and seal older deposits beneath more recent ones.

Now what is really awesome about this is the things you can deduce. Sometimes you will find evidence of cooking but no bones. That’s because cooking shrinks bone, sometimes to the point where the bone completely disappears from the archaeological record. That’s crazy! The bones that do survive cooking will become brittle and appear white or light blue in color. I saw this at my first dig in a cave in Lyon, France. Bluish bone was recovered in modest amounts, evidence that cooking was being done inside the cave.

The presence of horn, mollusk, shells, and turtle shells may signify the use of these as drinking vessels or bowls. And speaking of turtles, here’s an interesting tidbit: Sometimes turtles enter middens (refuse heaps) but there is no evidence of them. The way you deduce they were there is through the presence of commensals, such as barnacles and bryozoans, tiny invertebrate animals that are filter feeders. Both barnacles and bryozoans live attached to turtles and sea whales. So if you find barnacles or bryozoans at a site, you can deduce that a turtle (or sea whale!) must have passed or swum by!

Now a final note on commensals, this time land snails and house mice. Commensals are attracted to refuse heaps for food, moisture, and shelter. The presence of commensals at a refuse heap means the midden was left exposed to the elements for a long period of time. If there are no commensals, then this means that the pit “was filled rapidly, covering and protecting the refuse from disturbance and destruction by exposure to environmental forces (Armitage and West 1985; Reitz 1994a).”

Another thing that I found curious is how trampling can widely disperse an animal’s remains while leaving them scratched and broken. I can’t imagine walking over animal bones, but there you have it: Homo sapiens at its finest. Heavy foot traffic such as in a house, barnyard, or stable would be places where heavy trampling occurs. But the archaeologist has to be careful to distinguish trampling marks from marks made by the matrix in which the deposits are found. Again, from the Zooarchaeology book:

“When the soil matrix is coarse and has large sand grains, such scratches are easily visible without magnification. However, if the matrix is soft material, such as dried leaves and pine needles, the specimen’s surface may be so polished that it is similar in appearance to worked bone. Attributing such abrasions to trampling may be incorrect because similar marks also are caused by sedimentary particles, aeolian processes, or aquatic transport (Gifford 1981; Shipman and Rose 1983a).”

And let’s remember that plant roots can also leave marks on the specimens and burrowing animals can scratch and “rearrange” the position of the same.

What’s interesting about taphonomy are their studies. These are called actualistic studies. I know of a taphonomist, for instance, who released the bones of cows at a section of a river in Wyoming and then followed them down to see where they ended up. People, however, can get very creative with these studies. Again, from the Zooarchaeology book:

“In an experiment to document the impact of digestion on fish elements, Wheeler and Jones (1989: 69-75) fed fish to a dog, a pig, and a rat, as well as eating some themselves. They then collected the feces, sieved out the fish remains, and examined them for damage from chewing and digestion. The kinds of damage observed were then compared with those seen in an archaeological deposit of a latrine pit from Coppergate, York. This study of the survival rate of bone first fragmented by chewing and then exposed to digestive juices demonstrates that as much as 80 percent is lost.”

To go through your own feces in the name of science shows dedication and passion.

I’ve really had a wonderful day thus far reading about taphonomy, and this is definitely a branch of paleontology I would like to learn much more about.